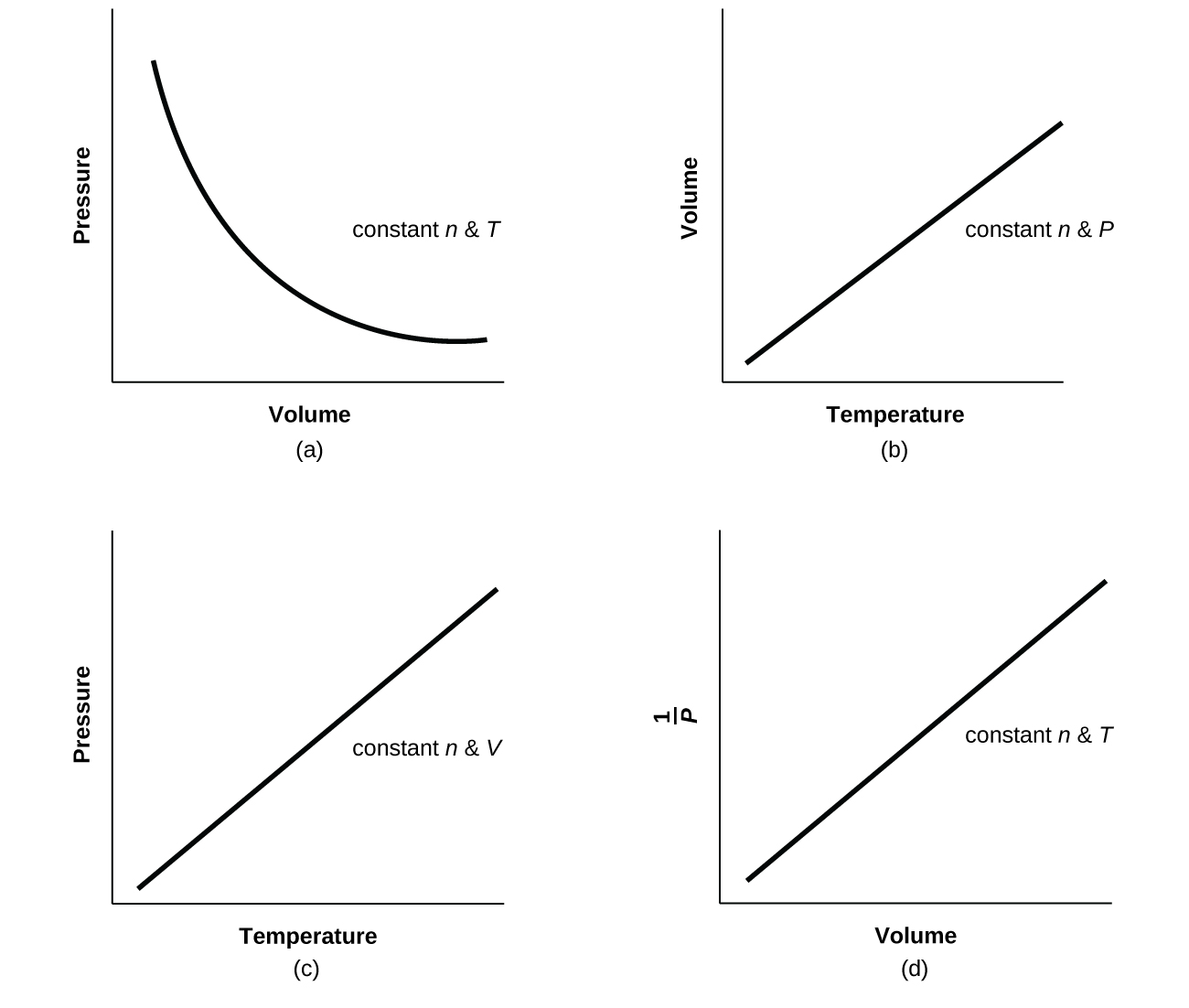

The behavior of gases can be described by several laws based on experimental observations of their properties. The pressure of a given amount of gas is directly proportional to its absolute temperature, provided that the volume does not change (Amontons's law). The volume of a given gas sample is directly proportional to its absolute temperature at constant pressure (Charles's law).

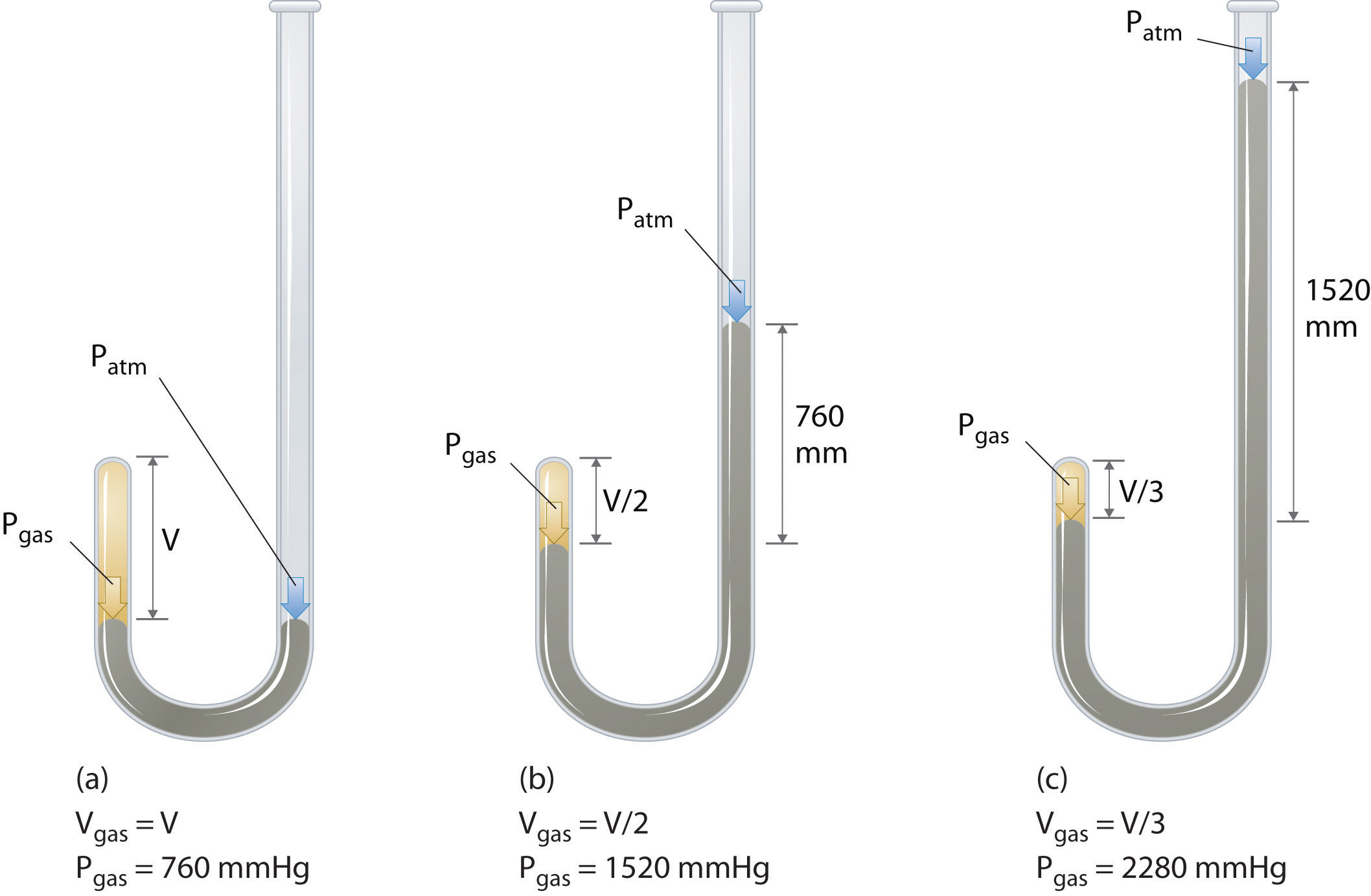

How Do You Measure Volume Of A Gas The volume of a given amount of gas is inversely proportional to its pressure when temperature is held constant (Boyle's law). Under the same conditions of temperature and pressure, equal volumes of all gases contain the same number of molecules (Avogadro's law). The physical properties of gases are very simple and identical for all gases. These properties of different gases are evident from the fact that all gases generally obey some simple or common gas formula or relation. After knowing these experimental ideal gas laws, a theoretical model-based structure of gases was developed in kinetic theory.

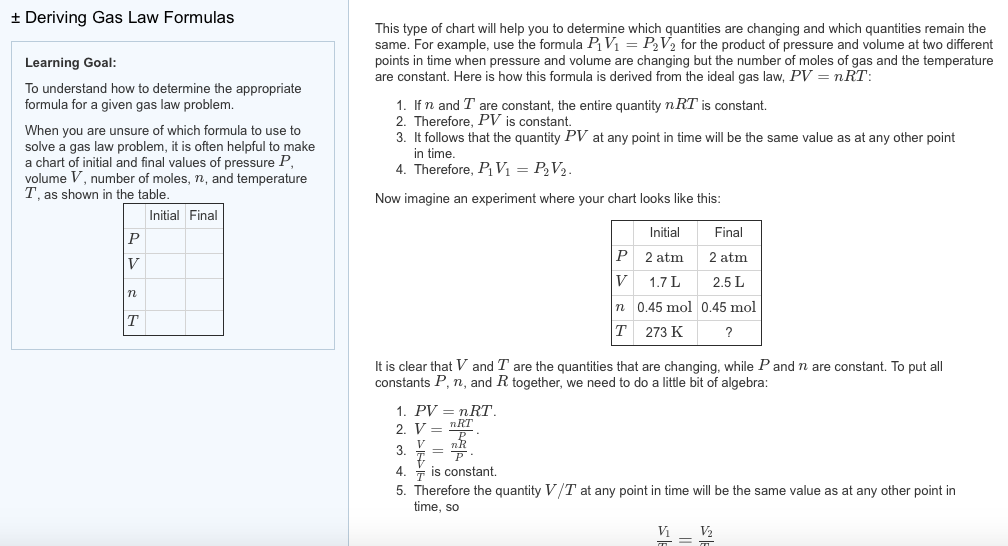

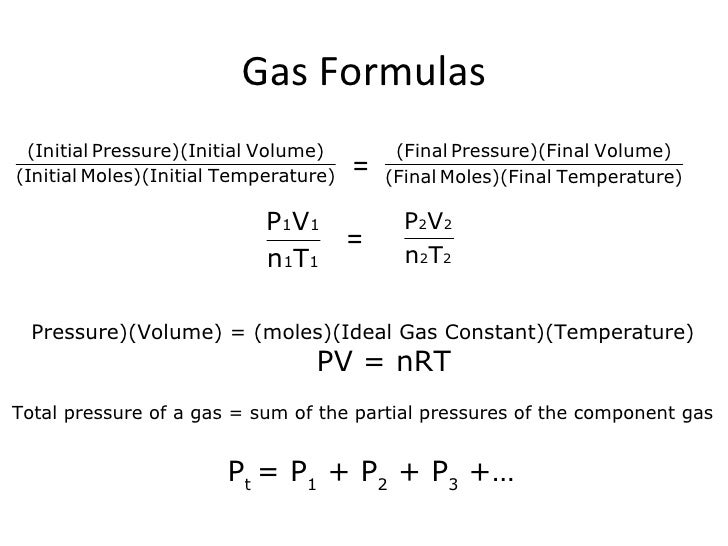

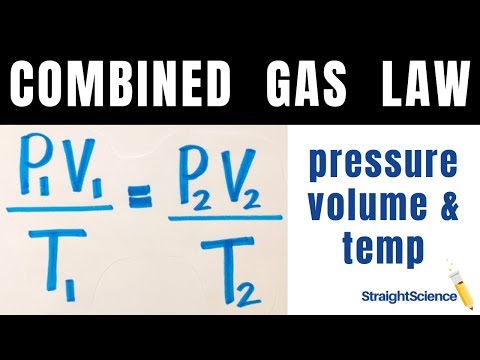

Eventually, these individual laws were combined into a single equation—the ideal gas law—that relates gas quantities for gases and is quite accurate for low pressures and moderate temperatures. We will consider the key developments in individual relationships , then put them together in the ideal gas law. Avogadro's Number, the ideal gas constant, and both Boyle's and Charles' laws combine to describe a theoretical ideal gas in which all particle collisions are absolutely equal. The laws come very close to describing the behavior of most gases, but there are very tiny mathematical deviations due to differences in actual particle size and tiny intermolecular forces in real gases. Nevertheless, these important laws are often combined into one equation known as the ideal gas law. Using this law, you can find the value of any of the other variables — pressure, volume, number or temperature — if you know the value of the other three.

Gases whose properties of P, V, and T are accurately described by the ideal gas law are said to exhibit ideal behavior or to approximate the traits of an ideal gas. An ideal gas is a hypothetical construct that may be used along with kinetic molecular theory to effectively explain the gas laws as will be described in a later module of this chapter. Although all the calculations presented in this module assume ideal behavior, this assumption is only reasonable for gases under conditions of relatively low pressure and high temperature. In the final module of this chapter, a modified gas law will be introduced that accounts for the non-ideal behavior observed for many gases at relatively high pressures and low temperatures. Using this calculator, you can calculate the molar volume of a gas for arbitrary temperature and pressure.

Just note that for big values real gases divert from ideal gas law (that's why they are not "ideal") and this formula can't be used. It is an intuitive idea that bubbles of air will expand if you heat them, as long as the pressure remains constant. It is also a fundamental component of the ideal gas laws, first written down in the early 19th century by the French natural philosopher Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac. Boyle's law is named after Robert Boyle, who first stated it in 1662. Increasing the amount of space available will allow the gas particles to spread farther apart, but this reduces the number of particles available to collide with the container, so pressure decreases.

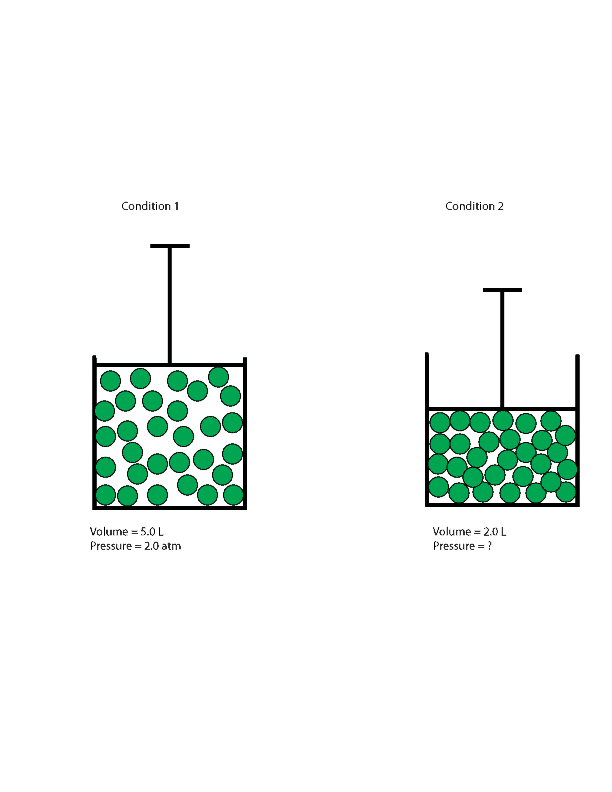

Decreasing the volume of the container forces the particles to collide more often, so pressure is increased. As more air goes in, the gas molecules get packed together, reducing their volume. As long as the temperature stays the same, the pressure increases. The ideal gas law specifies that the volume occupied by a gas depends upon the amount of substance as well as temperature and pressure.

Standard temperature and pressure -- usually abbreviated by the acronym STP -- are 0 degrees Celsius and 1 atmosphere of pressure. Parameters of gases important for many calculations in chemistry and physics are usually calculated at STP. An example would be to calculate the volume that 56 g of nitrogen gas occupies. First, we must determine the question, which is to calculate the volume of a quantity of gas at a given temperature and pressure. In a second step, after establishing a basis, we must convert the mass of methane that will be the basis into pound moles. Third, we must convert temperature in degrees Fahrenheit into absolute degrees Rankin and, fourth, convert pressure from psig into psia.

Fifth, we must select the appropriate ideal gas constant and use it with a rewritten form of Equation 4.11 to determine the volume of 11.0 lbs of methane gas. Finally, we can substitute the values previously determined into the rewritten equation to calculate the volume. The volume and temperature are linearly related for 1 mole of methane gas at a constant pressure of 1 atm. If the temperature is in kelvin, volume and temperature are directly proportional. Charles's law states that the volume of a given amount of gas is directly proportional to its temperature on the kelvin scale when the pressure is held constant. Plots of the volume of gases versus temperature extrapolate to zero volume at −273.15°C, which is absolute zero , the lowest temperature possible.

Charles's law implies that the volume of a gas is directly proportional to its absolute temperature. Previously, we considered only ideal gases, those that fit the assumptions of the ideal gas law. When pressure is low and temperature is low, gases behave similarly to gases in the ideal state.

When pressure and temperature increase, gases deviate farther from the ideal state. We have to assume new standards, and consider new variables to account for these changes. A common equation used to better represent a gas that is not near ideal conditions is the van der Waals equation, seen below. The state of a gas is determined by the values of certain measurable propertieslike the pressure,temperature,andvolumewhich the gas occupies. The values of these variables and the state of the gas can be changed.

On this figure we show a gas confined in a blue jar in two different states. On the left, in State 1, the gas is at a higher pressure and occupies a smaller volume than in State 2, at the right. We can represent the state of the gas on a graph of pressure versus volume, which is called ap-V diagramas shown at the right. In some of these changes, we do work on, or have work done by the gas, in other changes we add, or remove heat.

Thermodynamics helps us determine the amount of work and the amount of heat necessary to change the state of the gas.Notice that in this example we have a fixed mass of gas. We can therefore plot either thephysical volumeor thespecific volume, volume divided by mass, since the change is the same for a constant mass. And is a proportionality constant that relates the values of pressure, volume, amount, and temperature of a gas sample. The variables in this equation do not have the subscripts i and f to indicate an initial condition and a final condition. The ideal gas law relates the four independent properties of a gas under any conditions.

The ideal gas law formula states that pressure multiplied by volume is equal to moles times the universal gas constant times temperature. This relationship between temperature and pressure is observed for any sample of gas confined to a constant volume. An example of experimental pressure-temperature data is shown for a sample of air under these conditions in .

An example of experimental pressure-temperature data is shown for a sample of air under these conditions in Figure 9.11. Careful experiments show that the ideal gas laws are only approximately obeyed by different gases. The gases which do not obey these laws are called real gases. The ideal gas equation can be used to distinguish between ideal gas and real gas. The gas which obeys this equation is called ideal gas and which does not obey this equation is called real gas. Van der Waals equation was used to derive the properties of real gases.

The last column in the table above summarizes the results obtained when this calculation is repeated for each gas. The number of significant figures in the answer changes from one calculation to the next. But the number of molecules in each sample is the same, within experimental error. We therefore conclude that equal volumes of different gases collected under the same conditions of temperature and pressure do in fact contain the same number of particles. All ideal gases conform, in behavior, to a particular relationship between pressure, volume, moles, and temperature as dictated by the ideal gas law. The attraction or repulsion between the individual gas molecules and the container are negligible.

Further, for an ideal gas, the molecules are considered to be perfectly elastic and there is no internal energy loss resulting from collision between the molecules. Such ideal gases are said to obey several classical equations such as the Boyle's law, Charles's law and the ideal gas equation or the perfect gas equation. We will first discuss the behavior of ideal gases and then follow it up with the behavior of real gases. We have just seen that the volume of a specified amount of a gas at constant pressure is proportional to the absolute temperature.

In addition, we saw that the volume of a specified amount gas at a constant temperature is also inversely proportional to its pressure. We can correctly assume that pressure of a specified amount of gas at a constant volume is proportional to its absolute temperature. Let us also add the fact that the volume at constant pressure and temperature is also proportional to the amount of gas. Similarly, the pressure at constant volume and temperature is proportional to the amount of gas. Thus, these laws and relationships can be combined to give Equation 4.10. The relationships between these so-called "state properties" of a gas make sense intuitively.

But the ideal gas law can also be derived mathematically, from first principles, by imagining particles bouncing around a box. In essence, this meant looking at the properties of huge numbers of tiny components or particles inside a system in order to calculate the macroscopic results. In other words, a box containing a gas will have trillions of particles flying around inside it in random directions, bouncing off each other and off the walls.

Where Z is the gas compressibility factor, which is a useful thermodynamic property for modifying the ideal gas law to account for behavior of real gases. The above equation is basically a simple equation of state . As the pressure on a gas increases, the volume of the gas decreases because the gas particles are forced closer together. Conversely, as the pressure on a gas decreases, the gas volume increases because the gas particles can now move farther apart. Boyle's law states, at a constant temperature, the volume of a definite mass of a gas is inversely proportional to its pressure. Therefore, the volume of a given quantity of gases, at constant temperature equilibrium with the pressure of gases.

At constant temperature and 1 atm pressure, a cylinder contains 10 ml of methane or hydrogen gas. If the pressure increases to 2 atm then according to Boyle's Law volume decreases to 5 ml. Recall that the number of moles, n, is equal to the mass of the gas divided by its molar mass. Substituting this relationship into the ideal gas equation, and then rearranging, yields an expression for mass over volume or density. To apply this gas law, the amount of gas should remain constant. As with the other gas laws, the temperature must be expressed in kelvins, and the units on the similar quantities should be the same.

Because of the dependence on three quantities at the same time, it is difficult to tell in advance what will happen to one property of a gas sample as two other properties change. If a sample of gas has an initial pressure of 1.56 atm and an initial volume of 7.02 L, what is the final volume if the pressure is changed to 1,775 torr? Assume that the amount and the temperature of the gas remain constant. Kinetic particle reasoning - increasing the temperature increases the kinetic energy of the molecules giving more forceful collisions which push out the gas at constant pressure.

There are a number of chemical reactions that require ammonia. In order to carry out the reaction efficiently, we need to know how much ammonia we have for stoichiometric purposes. Using gas laws, we can determine the number of moles present in the tank if we know the volume, temperature, and pressure of the system.

Equal volumes of four different gases at the same temperature and pressure contain the same number of gaseous particles. Because the molar mass of each gas is different, the mass of each gas sample is different even though all contain 1 mol of gas. The pressure in the freezer is atmospheric pressure, the temperature in the freezer is lower that the outside temperature, so the volume of the balloon decreases when it is placed into the freezer. According to this equation, the pressure of a gas is proportional to the number of moles of gas, if the temperature and volume are held constant.

Because the temperature and volume of the O2 and N2 in the atmosphere are the same, the pressure of each gas must be proportional to the number of the moles of the gas. Because there is more N2 in the atmosphere than O2, the contribution to the total pressure of the atmosphere from N2 is larger than the contribution from O2. The main issue of concern with the Ideal Gas Law is that it is not always accurate because there are no true ideal gases. The governing assumptions of the Ideal Gas Law are theoretical and omit many aspects of real gases.

For example, the Ideal Gas Law does not account for chemical reactions that occur in the gaseous phase that could change the pressure, volume, or temperature of the system. This is a significant concern because the pressure can rapidly increase in gaseous reactions and quickly become a safety hazard. Other relationships, such as the Van der Waals Equation of State, are more accurate at modeling real gas systems. While ideal gases are strictly a theoretical conception, real gases can behave ideally under certain conditions.

Similarly, high-temperature systems allow for the gas particles to move quickly within the system and exhibit less intermolecular forces with each other. Therefore, for calculation purposes, real gases can be considered "ideal" in either low pressure or high-temperature systems. If a sample of gas has an initial pressure of 375 torr and an initial volume of 7.02 L, what is the final pressure if the volume is changed to 4,577 mL?

Assume that amount and the temperature of the gas remain constant. If we partially fill an airtight syringe with air, the syringe contains a specific amount of air at constant temperature, say 25 °C. This example of the effect of volume on the pressure of a given amount of a confined gas is true in general. Decreasing the volume of a contained gas will increase its pressure, and increasing its volume will decrease its pressure. In fact, if the volume increases by a certain factor, the pressure decreases by the same factor, and vice versa. Volume-pressure data for an air sample at room temperature are graphed in .

Imagine filling a rigid container attached to a pressure gauge with gas and then sealing the container so that no gas may escape. If the container is cooled, the gas inside likewise gets colder and its pressure is observed to decrease. Since the container is rigid and tightly sealed, both the volume and number of moles of gas remain constant.

If we heat the sphere, the gas inside gets hotter () and the pressure increases. Volume-pressure data for an air sample at room temperature are graphed in Figure 9.13. If we heat the sphere, the gas inside gets hotter (Figure 9.10) and the pressure increases.

The molar volumes of all gases are the same when measured at the same temperature and pressure (22.4 L at STP), but the molar masses of different gases will almost always vary. The ideal gas equation contains five terms, the gas constant R and the variable properties P, V, n, and T. Specifying any four of these terms will permit use of the ideal gas law to calculate the fifth term as demonstrated in the following example exercises.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.